|

[Note: This is by no means meant to be a complete history of the Pelikan

pen or the Günther Wagner firm. Readers seeking the fullest account

of Pelikan should consult Jürgen Dittmer and Martin Lehmann’s Pelikan

Schreibgeräte. A list of sources and additional reading is to be

found at the end of this piece. Rather this is meant to be a readable introduction

to Pelikans for beginning collectors and newcomers]

The history of Pelikan begins with Germany's industrial revolution in

the early nineteenth century and continues into the global economy of today.

During that period, the firm has consistently been a technological leader,

even as its fortunes rose and fell. In 1863 Günther Wagner became partner

in a business founded by Carl Hornemann of Hannover, a member of the newly

empowered German parliament. Since 1838, the firm had been producing artist’s

supplies using the newly developed technology of chemical dyes, a field in

which Germany led the world. Eight years later Wagner took over the business

giving it his name and expanding it into office supplies. In 1878, Wagner added

the name of Pelikan, from one of the elements in his family crest. Following

Wagner’s retirement, a decade later, his son-in-law and successor Fritz

Beindorff led the company to become one of the world’s leading makers

of fountain pens.

Although Wagner was late to enter the field, they revolutionized the manufacture

of German fountain pens with the first piston filler. Today, collectors from

around the world put huge amounts of money, time, and energy into collecting

what began as a homely little expression of German modernist pen design.

1st year pen—From

the collection of Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas. Jade 1929 pen.

The first Pelikan fountain pen was introduced in 1929 and was something different

in the world of pens. It had to be, for the firm had come to the market late

but with a remarkable innovation in filling systems.

Compared to most fountain pens of the 1920s, the original eyedropper-filler

had been highly efficient with only two moving parts and a large capacity.

But it was messy, cumbersome and time consuming. As early as 1905 Evelyn Andros

de la Rue developed a piston filler but, according to Andreas Lambrou, it was

a cumbersome device that did not catch on beyond the firm’s own products.

By the mid 1910s, the sac and the various devices used to compress it had become

the dominant filling system in England and America. But sacs took up space

and required an actuating mechanism, be it a lever and pressure bar, a crescent,

a button or any of dozens of other attempts to devise an elegant and effective

filler. In Germany and throughout the continent, a variant of the eyedropper,

the so-called safety pen, dominated.

So, by the late 1920s penmakers were ready to go beyond the eyedropper and

the sac, but where? This was an age of innovation, so on various fronts in

Europe and the United States the search was on for a system that would let

the barrel itself contain the ink with some device to fill it. The rod and

seal was one approach, taken by Omas, Onoto and Sheaffer, the diaphragm was

another, used most successfully by Parker and by Waterman and Osmia.

Then came the piston. An eastern European engineer,

Theodor Kovacs appears to have been the first to devise the modern piston filler

and secured a patent for it, probably in 1925. Kovacs’ design used a

shaft mounted with a cork seal as a piston and a telescoping device attached

to a turning knob to advance and retract it.

Exploded view - image

courtesy of Pelikan

In order to produce a pen based on his innovation, he went into partnership

with two brothers, Edmund and Mavro Moster, who controlled the Croatian firm

Penkala. By 1927, however, the Mosters were in financial difficulties and Kovacs

sold his patent to Günther Wagner. Two years later the first Pelikan was

produced and within five years of its release the telescoping piston filler

revolutionized European pen manufacture, replacing the favored safety filler.

Before long, even the giant, Montblanc, was forced to adopt the piston filler,

touching off a generation of close and often litigious rivalry between the

two firms.

Initially, however, their relationship was much more cooperative. Beginning

in 1924, Montblanc relied on Pelikan for ink, and Pelikan, which did not have

its own metal working facilities before 1935, relied on Montblanc for nibs.

How long that relationship lasted, whether for only the first year, or until

the mid-1930s is not clear. Today, the early Pelikan nibs, whoever made them,

are most highly prized by collectors. Those nibs, especially the flexible obliques,

define the Pelikan pen.

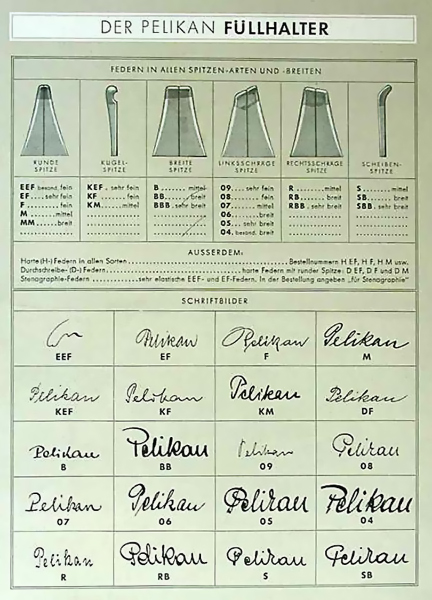

from the collection of

Gerhard Brandl/photography by Gerhard Brandl. The classic Pelikan nib chart.

Despite the economic woes of Germany, which were only heightened by the worldwide

Depression that hit the United States in 1929 and Europe the next year, Pelikan

prospered. The firm’s success came for a number of reasons. Foremost

was the firm’s worldwide reputation as a respected maker of artist supplies

and office products for more than fifty years. Related to this was the firm’s

ability to aggressively market and promote the pens. Finally, there was the

product itself.

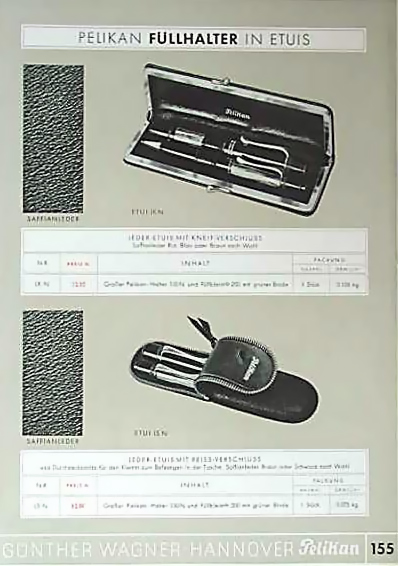

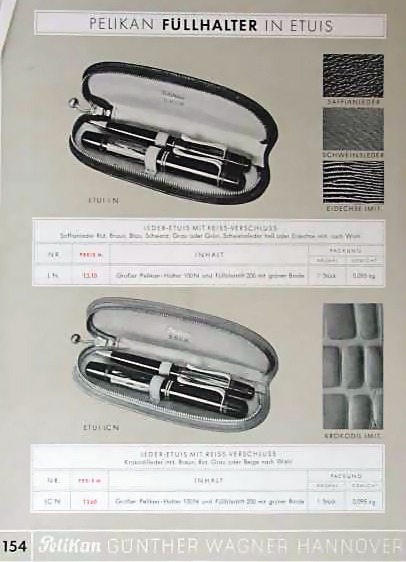

from the collection of

Gerhard Brandl/photography by Gerhard Brandl. Circa 1938.

from the collection

of Gerhard Brandl/photography by Gerhard Brandl. Circa 1938.

The Pelikan 100 was a model of simplicity from top

to bottom, the epitome of form following function. (The number 100, by the

way, was only adopted in 1931 to distinguish it from subsequent models.) The

pen was also a superb example of the German modernist style, which later spawned

the more widely known Bauhaus movement. Pelikan took advantage of this in their

early advertising, stressing the pen as a product of modern industrial design

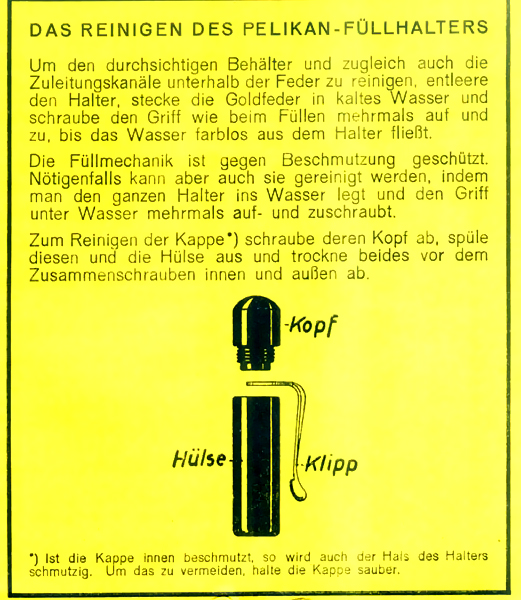

and illustrating the point with exploded diagrams. The high captop, designed

primarily to serve as an inner cap, screwed into the plain, unadorned cap tube

(the first models had no cap rings), and leaflets included with the early pens

showed users how to disassemble the cap to clean it.

The washer clip (or as Pelikan called it the drop clip) married form and function

perfectly. Easy to remove or replace if damaged, the sleek, distinctive style

modernistically evoked the shape of the bird’s beak, and represented

Pelikan to the world until after World War II when the clip came to more closely

resemble a pelican’s beak.

from the collection of

Gerhard Brandl/photography by Gerhard Brandl. A tray of Pelikans from 1929

and 1931

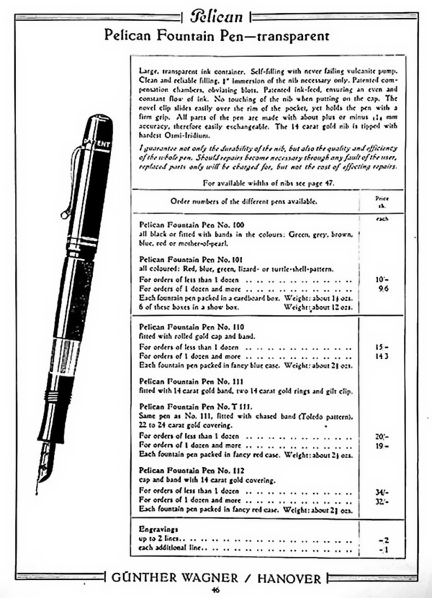

from the collection of

Gerhard Brandl/photography by Gerhard Brandl. English language catalog

Circa 1934.

The rest of the pen, the body or shaft, made from bakelite, was a simple

one piece tube (this would change after the first year when they went to celluloid

and hard rubber construction) with the nib assembly at one end. At the other

end a three-piece filler mechanism reverse threaded into the barrel. There

was the so-called cone which was a keeper for the filler itself consisting

of a hollow shaft and piston. The piston then telescoped into a solid shaft

attached to the knurled filler knob stamped with an arrow to indicate the direction

to turn at the other. That was it. The only decoration came with the distinctive

barrel band (in German, the Binde), to this day a feature of the top-line Pelikans.

100s—From the collection

of Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas.

Tray of early Pelikans in various

colors, 1929-1934.

Initially, the pen came in two versions, first was the jade green (similar

to Sheaffer’s green) with the unadorned black hard rubber cap.

Photography by David

Isaacson, pen from the collection of Rick Propas. (1929)

That was followed by the traditional German black, with the celluloid Binde

and the plain black cap. According to legend, the conservative German business

class favored black pens

Photography by David

Isaacson, pen from the collection of Rick Propas. (1929)

because the earliest hard rubber pens had been of that color. Unlike Americans

who thronged toward the rainbow of colors first made possible by the advent

of celluloid in the mid-1920s, Germans had to be coaxed in that direction.

Pelikan did their best.

Among these early pens there seem to have been infinite variations of green,

but the early green Bindes can be lumped into three types, the familiar marbled

green (marmoriert), the much less common early jade, which looks like the Sheaffer

green, and a variant of the marbled green made from cut strips of celluloid

laminated together.

Photography by David

Isaacson, pen from the collection of Rick Propas.

The question of variations in color is a more complex

one. In many cases time has faded and shifted colors, so that today we have

all sorts of shades of green, from near grey to olive to still brilliantly

true colors, but as they were produced the first pens were green, plain and

simple, and there was black. Pelikan hedged their bets against German conservatism.

Green 100s—From

the collection of Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas.

Within a few years Pelikan also entered the market for low priced school

pens with first the Rap-pen and then the Ibis, later to be followed by the

120, 140 and Pelikano.

Between 1929 and 1933, when the design of the 100 settled,

for at least a few years, into the form we know, the pens underwent a dizzying

series of developments. Those who should know better often claim that it’s

easy to collect Pelikans because there was only one model. To those of us who

pursue the elusive early birds there is a dizzying array of variants--plain

caps and caps with bands; caps with a single pair of vents and double vents;

cylindrical captops and tapered captops; barrels made of bakelite, barrels

made of celluloid and barrels made of acrylics; sections that are straight

and sections that taper, feeds with three even vanes and feeds with a recessed

center vane. You get the idea, and I haven’t even begun to talk about

the real arcana, for example the section to inner cap seals. Through all these

changes, month by month Pelikan was tweaking the design and function of the

pen.

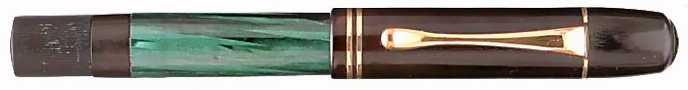

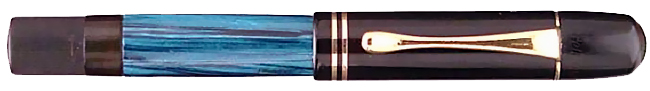

Then came form. Possibly as early as 1930, but certainly

by 1931, Pelikan decided to produce their basic pen for the luxury market,

which, despite hard times, still existed. The 111 was probably the first of

these. It featured a guilloched 14 karat solid gold band over the basic celluloid

shaft. The rest of the pen was the standard black hard rubber. The 110, despite

its earlier number, came next with a white gold-filled cap, captop and barrel.

Only the black turning knob remained uncovered. This was followed by the 112,

which was all 14 Karat gold covered (except for the mechanism). Most famously,

the T111 offered a steel Binde (not the sterling of the later 700 and 900 models)

that was worked in the elaborate and painstaking Moorish-influenced, Toledo

metalworking style.

Toledo images courtesy

of ChartPak

Heavy Metal—From

the collection of Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas.

According to company history, all these models came in 1931 and not later,

as commonly assumed. Later in the decade, outside jewelers, most notably Maenner,

produced authorized models that were more ornate and completely clad, top to

bottom.

And then there were the less common celluloids in two styles. The basic 100

featured colored Bindes in gray, red, yellow, blue, and brown marbled.

Blue 100 - Photography

by David Isaacson, pen from the collection of Rick Propas.

There was also a tortoise shell with red hard rubber cap and mechanism.

RHR Tortoise 100 - Photography

by David Isaacson, pen from the collection of Rick Propas

These variants seem not to have been produced in large numbers and may have

been marketed and sold mostly outside Germany. Today, when these uncommon pens

become available they frequently fetch a ransom. The number 101 designated

all-celluloid pens (except, as always, the turning mechanism). These pens came

in lizard and tortoise, as well as red, green and blue. The latter colors resemble

not the marbled bands of the “regular” pens, but the jades, lapis

and corals of American makers.

Coral 101: from the collection

of Gerhard Brandl/photography by Gerhard Brandl.

Lizard 101—From

the collection of Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas.

These pens rival 110s, 111s and 112s in value and seem much less common.

With these successes, beginning in 1934 Pelikan expanded. First came a mechanical

pencil, the 200, as well as a less common variant, the short 210, both marketed

as the “Auch Pelikan” or “Pelikan, too.” Put simply

the design of the pencil was the “clicker.” The pencil also has

its own arcana in terms of markings and materials. In the interests of sanity,

we’ll let that go for now. Like the pen, the pencil was relatively advanced,

especially in comparison to the simple, even primitive, propel/repel pencils

produced by other German makers such as Kaweco and Osmia.

Over the next three years, Pelikan began to seriously revise their product

line for reasons that were both technical and market driven. Around 1937 Pelikan

replaced the yellow celluloid barrel with one of green plastic, a material

that was more easily workable.

That was just the beginning. Although Pelikan by now was reknowned for the

beauty of their celluloid Bindes, hard rubber was the basis for most of the

pen, apart from the shaft. Hard rubber was and is an unstable compound, essentially

sulphurated rubber, susceptible to water damage and oxidation. Earlier pen

makers had used other materials, such as bakelite and Pelikan had used it briefly

for the shafts of their earliest pens. But bakelite is heavy and brittle and

like hard rubber does not take color well.

Beginning with Sheaffer in 1926, celluloid came to dominate the manufacture

of pens until after World War II. From the start, Pelikan had used celluloid

for the Bindes of most of their non-metal pens. After 1930 the bodies of the

pens were of celluloid, but Pelikan stayed with hard rubber for the caps and

captops until 1937 or 1938. Then, gradually, they began moving toward celluloid,

first for the cap tubes, then for the captops, and finally for the filler mechanisms.

Interestingly, Pelikan held onto the hard rubber machinery, which survived

the war and later surfaced in Milan (more on that later). The result is that

today many of the pens come down to us with mixed materials, a cap tube of

celluloid mated to a hard rubber captop. Some of these pens may be later “marriages”

but many are quite correct. Pelikan stayed with hard rubber for the mechanism

somewhat longer, and for good reason. Celluloid proved difficult to mill in

the distinctive manner of the Pelikan filler knob. They did produce a milled

celluloid knob for a few years before introduction of a 100 model with the

smooth knob (often erroneously designated the 100C), but by 1939, except for

foreign production, hard rubber was gone from Pelikans.

The second reason for Pelikan’s augmentation of its line had to do

with size. Compared to almost every pen of the time, the Pelikan 100 seemed

small. In use the pen was, in fact, much larger than it seemed, for the cap

posted high, creating a comfortable center of balance, and the gripping section

was thick, filling the hand. But there was no denying the relatively small

ink capacity when compared to larger pens.

In 1937, Pelikan introduced a new model. The 100N did

not replace the 100, which continued in production until Pelikan shut down

in 1944, but was offered alongside it. Interestingly, some of the early production

100Ns bear the characteristics of the early 100s, yellow celluloid barrels

and hard rubber sections, mechanisms, caps and captops. A few even have the

old Pelikan logo, which was not streamlined until a year later.

The 100N was offered in variations similar to the 100, although the “minor”

Bindes, yellow, red, brown and blue, were dropped, as were the red, coral and

jade 101s. What was left were the standard, green, black, gray, tortoise

and lizard. Moreover, by 1939, the precious metal models, if made, were no

longer catalogued. By then, of course, rising economic and political instability

began to seriously afflict all of Europe. By the latter part of the decade

Pelikan, under government edict, also curtailed the use of gold for nibs,

first at home and then abroad.

At the eve of World War II, Pelikan pens were

sold all over the world, including Europe, India and throughout South America,

but were manufactured in at least one site outside the country. The history

of foreign manufacture of Pelikans is obscure and something we hope to address

later this series, but we do know just a bit about it. Pelikan was certainly

not the only company to sell beyond their borders in the 1920s and 1930s. Montblanc,

Parker and Waterman all distributed and manufactured beyond their countries

of origin and Pelikan was well poised to follow suit as they were long since

established as makers and purveyors of office and art supplies. Beyond that

the story becomes a bit obscure.

There was one well-documented production facility in Danzig. More than any

other foreign plant, the products of the Langfuhr factory differed from the

Hannover products most notably in the distinctive diamond shaped clip and the

appearance during the war of the single cap band. Nibs may have been made there,

some of them bearing a distinctive round “P” logo.

Beyond Danzig, the record becomes far less clear. We know that Pelikan had

plants in Bucharest, Barcelona, Milan, Sofia, Vienna, Warsaw, Zagreb, Zürich,

and throughout South America, but mainly they produced ink and office supplies.

However, in every branch there were pen repair facilities that had spare parts

and out of those parts pens may have been assembled. According to Jürgen

Dittmer, that is the basis of the belief that Pelikan pens were produced in

Zagreb and elsewhere.

Then there are the so-called Emegê pens, stamped with the name of Pelikan’s

Portugal distributor. By one account, the Portugese Pelikan distributor, Leichsenring,

had an unusually lenient repair policy and found themselves fixing pens that

they had not sold, so they began “branding” their pens. But they

may also have sold exclusively one model, the “Magnum” oversize

100N. Many of these show up with the Emegê stamp, indicating that they

came out of Portugal. Where they were produced is another matter, whether Germany

or possibly the postwar Milan plant. Looking at the pens produced in these

locations, Danzig, Milan, Portugal, Zagreb, suggests that at least some parts

were locally produced.

World War II, of course, had an impact on Pelikan. However, they were able

to manufacture until the last year of the war when they closed down, it is

not clear whether by edict or because of material shortages. However, the rule

of the Nazis had its impact even before the war. As early as 1938 the German

government began limiting the use of gold and forcing export trade for the

purpose of securing hard currency. By 1938, many of Pelikan’s luxury

models could be sold only outside the country and in Germany pens could be

sold only with steel alloy nibs.

When Pelikan resumed production after the war, they initially continued producing

their prewar models, minus the 100. The same was true, by the way, all over

the world. The 1946 Ford, for example, is identical to the 1942 model, which

in the U.S. was the last prewar car made by that firm.

There were, however, postwar changes, mostly in materials. Gold for nibs

was again available, and many of the wartime Pd and CN nibs were swapped out

for postwar 14 karat nibs. These nibs, which may also have been made before

the war for export models, resembled the traditional nibs, except that the

imprint bore the word Pelikan in a plain rather than incised script. Also the

successor to the cork seal, which was first replaced by rubber during the war,

was now perfected. The new seals were made now of a clear elastomer. Finally,

the 100N lost the ridge that connected the hard rubber section to the celluloid

barrel on the early models and was now manufactured with a smooth, one piece

celluloid shaft just as the later 100s had been.

Two common variants of

the Pelikan 100N, with two narrow cap bands and regular drop clip and with

fluted cap band and clip. From the collection of Gerhard Brandl, photography

by Gerhard Brandl.

A variant of the Pelikan

100N was made without a clip to go smoothly into women’s purses.

These pens did not have the common ribbon ring often found on women’s

pens. From the collection of Gerhard Brandl, photography by Gerhard Brandl.

100Ns in tortoise, left

to right 100N tortoise and red hard rubber, uncommon 100N Magnum (oversize),

101N pen and pencil in celluloid, short captop late 101N. From the collection

of Rick Propas. Photography by Rick Propas

Foreign production was also resumed, this time only in

Milan and using old equipment for the manufacture of hard rubber pens imported

presumably from Hannover. Over the next few years, Milan produced not just

pre-war pens, but a number of variants. Some of the most interesting of these

pens were 100N pocket and desk pens made without a Binde. The colored celluloid

was integral to the barrel and not an overlaid band as had been the case with

virtually every Pelikan made up to that time. The nibs and clips were also

unique to the facility. Production in Milan did not last long, however, due

to quality issues. Today, the immediate postwar Milan pens are highly valued

by many of the more compulsive Pelikan collectors.

The postwar European economic miracle would take Pelikan to new heights.

As early as 1950 a new model, the 400, was introduced, as part of the most

thoroughgoing product redesign in the company’s history. At the same

time, though, Pelikan hedged their bets on both prosperity and postwar modernism

by introducing the 120, 140 and 300, lower cost lines based on the familiar

shapes of the Rap-pen and the Ibis. But the firm’s postwar fortune and

the design idiom that marks the top line Pelikans to this day would come with

the 400.

Pelikan 400s in green

and tortoise. From the collection of Gerhard Brandl, photography by Gerhard

Brandl.

Despite its new appearance, at its heart the 400 was

very much a Pelikan, featuring the same basic design as the 100. As before

the body of the pen was made up by a shaft covered by a Binde, now striped

rather than marbled. The cap was somewhat changed, now in four parts with a

tube, captop and beaked clip held to the captop by a washer, and, of course,

the signature piston filler, now redesigned and made entirely out of plastic.

In fact, take apart some of the early tortoise 400s, and you will even find

a yellow celluloid shaft, just like the earliest 100s. In automotive circles,

Porsche is reknowned for its conservative, yet stylish, design tradition, the

basic shape of the cars dating back to 1965. Today the so-called Souverän

Pelikans, the 300-1000 series, carry on a design originated even earlier, 53

years ago.

The postwar economic history of Pelikan is one of expansion followed by contraction.

The firm prospered through the 1950s and into the 1960s. However, the early

postwar era brought the ballpoint pen which began to catch up with Pelikan

as it did with virtually every other pen manufacturer. Nevertheless, between

1950 and 1963 Pelikan had a remarkable run, producing the 400 in nearly as

wide a range of colors and styles as it had the 100s and, one suspects, in

larger numbers. Like its early counterparts, the 400 can be surprisingly hard

to catalogue. Most commonly the pens were offered in the traditional green

and black, this time with stripes to provide a more visible ink supply. A somewhat

new model, in striped tortoise shell with brown cap and filling mechanism became

a most favored variant. In addition there were gray and mother-of-pearl models,

the latter looking like the pre-war tortoise 101 model in the shape of the

400s, but with the new brown rather than the red trim. The seagreen, not commonly

found today, was green striped, but with a dark green (rather than black) section,

cap and filler. According to Dittmer and Lehmann, there were also many prototypes

made in extremely small numbers, some of the most interesting with white and

yellow bodies. There was also an accountant’s pen, a traditional tortoise

model, but with a red captop to signify red ink. In addition there were the

models 500, with a gold filled cap; the 520, all gold-filled; the 600, with

14 K cap; and the 700, all 14 K. Sadly there was no white gold model.

From the collection of

Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas. Tray of Pelikan pens in tortoise.

Circa 1934-1987.

In 1955 change again came to Pelikan. This restyle,

however, was much less comprehensive than that of 1938 or 1950. The pen remained

essentially the same, only the new 400N was given a slightly larger cap and

a more rounded turning knob. According to most accounts this model was sold

only briefly but in a full range of colors and types. Why the pen was produced

for such a short time is anyone’s guess. In 1956 the last of the postwar

Pelikan models was introduced and would stay in production for seven years,

the 400NN. The 400NN, which kept the same barrel as the 400, was made in all

the colors of the 400.

At this point, I should note the narrow focus of this history. For the most

part I have not taken notice of the market segment that would carry most German

penmakers, the school pens. That, however, is a topic for another time. Nor,

as this story progresses, will I discuss the proliferating models—the

Signums, the Celebrys--that marked the period from 1970s to the present. They

are just too many, and in my view, they are but offshoots of the main Pelikan

branch. Interested readers are best referred to the most definitive history

of Pelikan, apart from the company’s own emerging web history, that of

Dittmer and Lehmann, cited at the end of this article.

from the collection of

Gerhard Brandl/photography by Gerhard Brandl. These are contemporary.

By the 1970s, Pelikan clearly was in trouble. The

pens of the 1960s, the M30-M100 series, had seen success to rival Montblanc,

but the pen market was declining. This can be seen in the proliferation of

the new models and the advent of outside management. Despite the success of

the 400 line and its offshoots, the ballpoint pen was the writing instrument

of choice in a fast changing world. Like many others, such as Parker, Pelikan

was slow to introduce its “Roller,” the ballpoint accompaniment

to the 400 series, which came only in 1955.

In this new environment, penmakers everywhere scrambled to make fountain

pens more relevant to the postwar world. Parker, of course, was one of the

most successful with its “51” model introduced during the war in

1941. It was followed by the 61 (this time without the quotation marks). The “51” pioneered

the hooded nib and set the idiom for fountain pens in the early postwar world.

It was also copied widely by firms like Aurora, Onoto and Platinum. Pelikan’s

answer was the P1. The pen was an awkward looking copy of the 61, but did incorporate

traditional Pelikan quality and some innovations from none other than Theodor

Kovacs who had developed the piston 40 years earlier. Still the pen offended

many Pelikan users and like the Parker 61 it used poorly made, lightweight

plastic. The model lasted only five years and was a failure according to Lambrou.

Alongside the P1 Pelikan launched a broad range of models, the most successful

of which was a new school pen, the Pelikano, first sold in 1959 and made to

this day.

Despite the fact that the company continued under the ownership of the Beindorff

family, in 1963 for the first time the family turned to outside management

from Hans-Joachim Götz. Like so many leaders of struggling corporations

in that era, Götz did more than simply develop new lines within traditional

markets, he took the firm more aggressively in the direction of an ever-wider

range of products including steps toward the emerging field of information

technology. One costly failure, emblematic of the challenges the firm faced,

was the attempt to enter the field of copiers. Pelikan’s product was

expensive and did not work well.

In the dying days of the industrial era and before the full emergence of

an information age, diversification for its own sake was not enough. Nor was

Pelikan unique. The merger mania of the 1970s and 80s took many businesses

away from their core markets in often vain efforts to survive economic change.

In 1976 new management continued the foray into wider markets, now to include

recreational products and even cosmetics. In 1978, the firm went public with

shares divided among family members and outside owners. By the early 1980s

the firm, still undercapitalized, was in trouble. Pelikan went into receivership

in 1982. Two years later it was taken over by the Swiss firm, Condorpart. In

1996, Goodace of Malaysia became majority stockowner of Pelikan.

As the firm collapsed, this time the new managers took

it back to its core, in 1982 reintroducing the 400 series, which had not been

produced since the 1970s revival of the NN produced under license by Merz & Krell,

mostly for the Asian market. The new 400 did well and, based on its success,

Pelikan began to reemerge as a premier penmaker. Through the 1980s the company

brought out a dizzying range of new products, including, in 1985, a new Toledo

based on the 400 but with an engraved vermeil Binde that evoked the firm’s

most famous design of the 1930s. There followed the 750 and 760 anniversary

pens, commemorating the firm’s 150th year, the sterling cap 730 of the

1990s, and many others. But, the most notable pen of the Pelikan renaissance

came in 1987 with the introduction of the M800.

Above and below: From

the collection of Henry C. Przygoda/photography by Henry C. Przygoda. Uncommon

Pelikan M800s in tortoise, circa 1987.

To then, the history of Pelikan had been a history of small, light pens.

Even as the company’s rivals, most notably Montblanc and Osmia, moved

toward larger pens as early as the 1930s, Pelikan remained with its core size,

ranging from the diminutive 4 3/4 inches of the 100 to a maximum of 5 1/4 inches

for the slender 400NN. The 800, with a smooth brass filling mechanism, was

neither small nor light and was, presumably, meant to go up against the larger

contemporary Montblanc149. The 800, first in traditional black and green and

all black, and then followed by an extremely small run of tortoise models,

and later blue and in red, aimed at the emerging prestige pen market so dominated

by the pens with the white star. Pelikan also used the 800 as a platform for

a whole raft of Limited and Special Editions, beginning with the M900 and 910

Toledos and the green transparents of the early 1990s and continuing to this

day. The 800 also inspired a number of custom penmakers who used the now famed

800 as a platform for authorised and unauthorised custom versions of the pen.

A decade later Pelikan again took on the legendary Montblanc 149 with an even

larger pen the M1000.

From the collection of

Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas. Pen made of Pelikan M800 components

sheathed in Titanium by Grayson Tighe, 2001.

Finally, in 1997, the firm launched the “Originals

of Their Time”

series. Beginning with an evocation of the 1931 111 gold banded model, over

the next six years the company released five pens in this series, three in

precious metals and two in celluloid, the green and blue 1935s. In 2003, the

series was concluded with its crown jewel, a Toledo that very closely followed

the 111T of the 1930s. As I have written elsewhere, the series was bold and

courageous, faithfully evoking the firm’s roots, that diminuitive first

pen. At a time when luxury pens screamed, “look at me, my owner is wealthy,” the

Originals sat demurely in desk or pocket reminding the user that this was a

firm which, through the twists and turns, the horror and change of the twentieth

century, survived by, for the most part, staying true to itself.

Note: Any history of Pelikan must rely on

two basic accounts, those of Jürgen Dittmer and Martin Lehmann in Pelikan

Schreibgeräte, and Andreas Lambrou, most completely in Fountain

Pens of the World. In addition, I have used Pelikan’s own company

history, available at ChartPak.

I also found helpful material in The PENnant (vol.XV, no.2, Summer

2001) which was devoted to Pelikan and which I edited. Other material on

pen history in general came from Bowen and Lambrou. There is a small amount

of useful Pelikan material in Miroslav Tischler’s Penkala Writing

Instruments. Regina Martini’s Pens &

Pencils is a good source for identifying models and for background.

I am indebted to Gerhard Brandl, Jurgen Dittmer, Martin Lehmann, Sharon Propas

and Len Provisor who read, commented and fact-checked this history. I, and

not they, however, am responsible for all errors, omissions and bad commas.

This article originally ran in four parts on PenTrace, and

can still be found there.

Text © 2003 Rick Propas. Photos © 2003 as indicated in captions. |